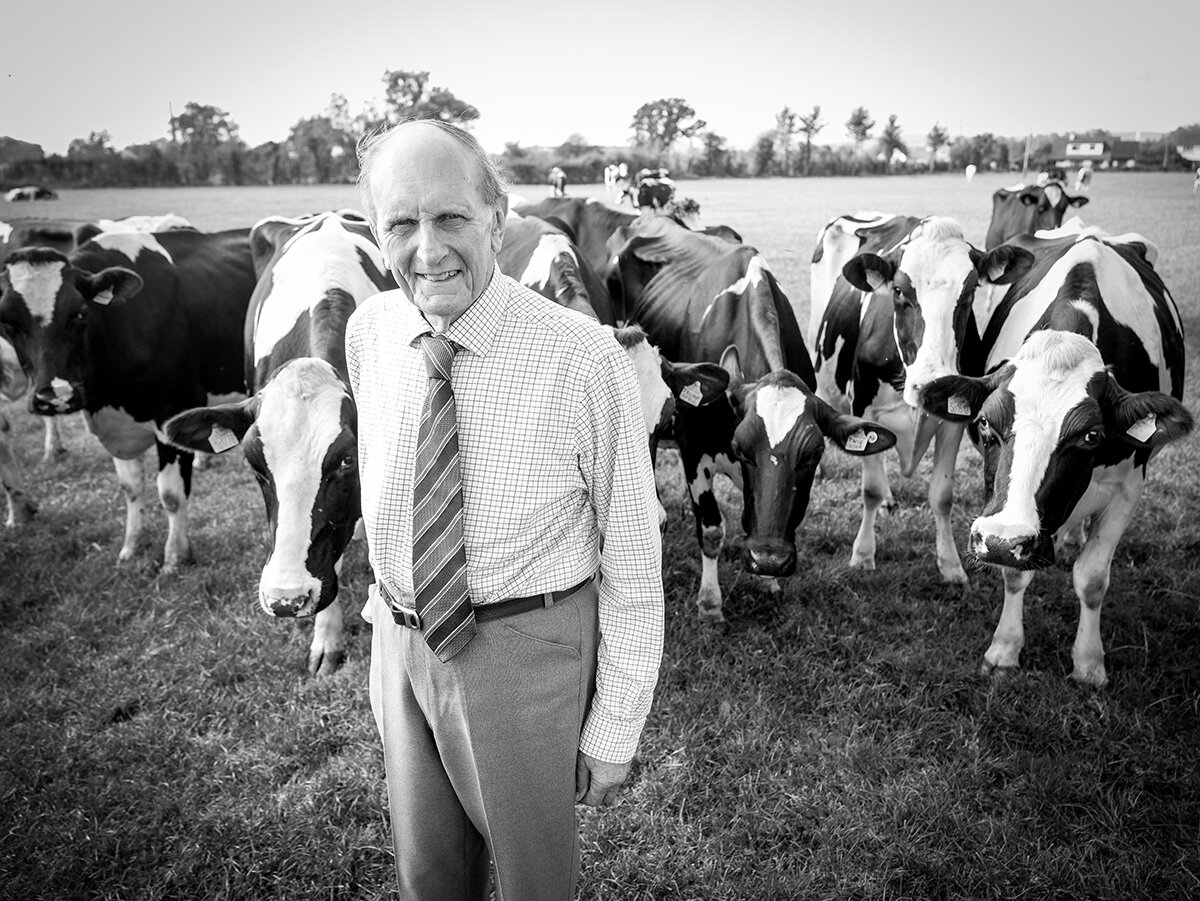

- Tony and Chris George, steel workers (Llanwern)

Tony and Chris George (Nanette Hepburn)

Richard Thomas & Baldwins’ steelworks was the first oxygen-blown integrated steelworks in Britain when it opened in Llanwern in 1962. At its height, it employed thousands of workers, and was spread over several miles of the Levels.

“People said if you managed to get a job in the steelworks you had a job for life,” says Chris George. “In Tony’s case this was right.”

Tony had left school at 16. “I had a job at Llanwern in 1960. Chris and I married in 1963 and were allocated a bungalow in Tennyson Avenue.” There was a strong sense of community. “We knew everybody from the start of the village to the end of the road.”

A fence separated Tennyson Avenue (also known as ‘Managers’ Avenue, for many senior staff from the works were housed in the Avenue), from the Steelworks, the beating heart of industrial Newport. The stock yard lights were so bright you could read the evening Argus at midnight in the garden. And when the wind blew the wrong way, red dust rained down: “I had to wash Tony’s clothes every day and you couldn’t put the washing out.”

Work was plentiful. “There was Whiteheads (where Chris worked as a computer tape operator), Braithwaite’s, Stewart and Lloyds, Standard and Telephones, Monsanto, British Aluminium. By the time you were 19, you could have had three or four jobs,” says Tony.

It did not last. “We were producing material and then, eventually, other people came along and started making it cheaper. Then the industry closed up.” Now, says Tony, “we know hardly anybody here now.”